In the world of healthcare, ultrasound scans are a common tool for physicians to visualize what’s happening inside the human body. However, structural engineers have faced challenges when trying to achieve a similar insight into concrete structures. Traditional methods for examining concrete, which is composed of various materials like stone, clay, and sand, have often fallen short in clarity due to sound wave scattering.

Excitingly, a collaboration between Japanese and American scientists has resulted in the development of a groundbreaking ultrasonic imaging system. This innovative technology allows for the detection of internal defects in concrete buildings and bridges without causing any damage to their integrity.

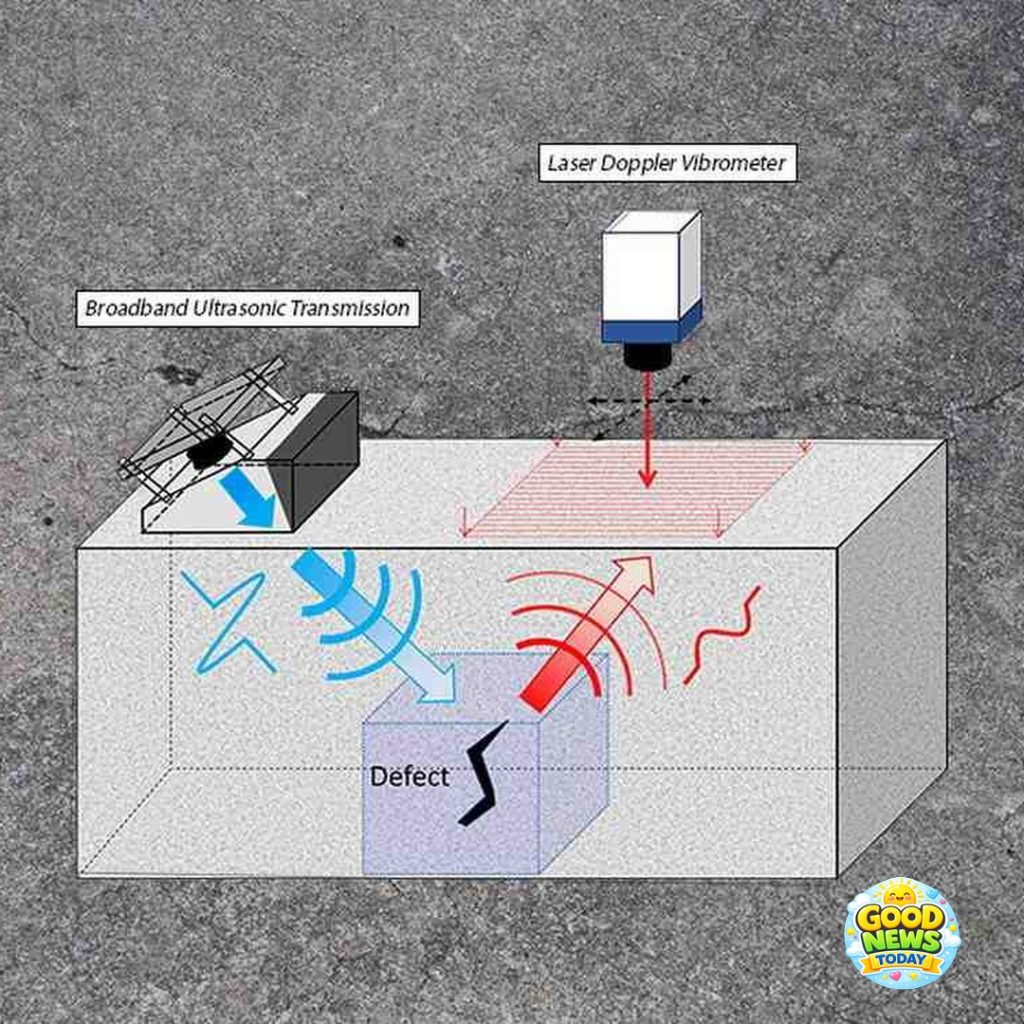

The team, including researchers from Tohoku University in Japan, Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico, and Texas A&M University, has created a method that sends sound waves into concrete and captures the returning echoes to generate internal images, much like an ultrasound does in medicine. Professor Yoshikazu Ohara from Tohoku University explained, “Our approach utilizes broadband ultrasonic waves that encompass a wide range of frequencies instead of relying on a single, fixed frequency.”

One of the key advantages of this system is its ability to automatically adjust the frequency to match the material being analyzed, enhancing the visibility of defects against the background of concrete. This adaptability is crucial since different components within the concrete can affect the transmission of various sound wave frequencies.

To tackle this complexity, the researchers employed two devices: one to generate a diverse range of frequencies and another—known as a vibrometer—to capture the waves that return from the concrete. This dual approach ensures that even when some frequencies are filtered out by the concrete, the system can still detect those that manage to penetrate.

With the capability to handle a wide spectrum of frequencies, the ultrasonic imaging system produces high-resolution 3D images of any defects along with their precise locations within the material. Professor Ohara noted, “As the concrete filters out certain frequencies, the laser Doppler vibrometer simply captures whatever frequencies remain. Unlike traditional systems, ours adapts automatically without needing to change transducers or adjust frequencies beforehand.”

This remarkable advancement offers invaluable information for repair planners and field technicians, detailing the size, depth, and three-dimensional extent of defects. Such insights can significantly enhance the efficiency of repair strategies, ensuring that structures remain safe and sound for years to come.

Share this inspiring achievement in materials science with your friends and family!