Today marks a remarkable milestone, as it was 56 years ago that George Harrison’s beloved song, My Sweet Lord, soared to the top of the UK pop charts. This iconic track also claimed the number one spot in various countries including the US, Ireland, Canada, Australia, Belgium, Sweden, Switzerland, West Germany, Japan, and many others. As Harrison’s debut single as a solo artist, it made history by being the first number-one hit from an ex-Beatle. The song serves as a heartfelt message advocating for spiritual unity, beautifully intertwining the Hebrew word “hallelujah” with a Vedic mantra honoring the Hindu deity Krishna.

The lyrics of My Sweet Lord resonate with Harrison’s deep longing for a personal connection with the divine, articulated in simple terms that can be embraced by individuals of all faiths.

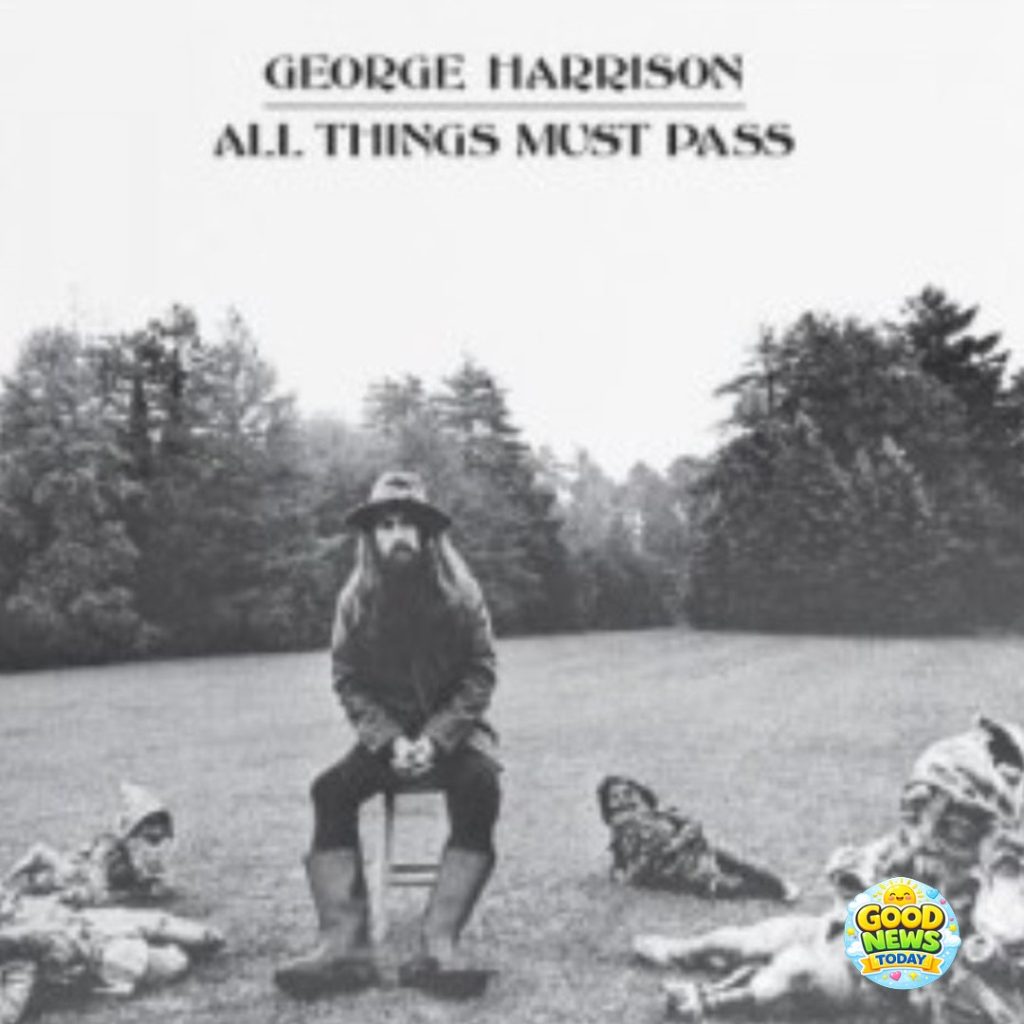

Interestingly, Harrison initially hesitated to release the song as a single. However, he eventually agreed to the wishes of Apple Studios, who believed that his triple album, All Things Must Pass, contained at least three potential hit singles.

Remarkably, the success of this single was achieved without any concert performances or promotional interviews from Harrison. Its widespread acclaim was driven largely by its powerful presence on the radio. As noted by Harrison’s biographer, Gary Tillery, the song “rolled across the airwaves like a juggernaut,” making a significant impact akin to Bob Dylan’s Like a Rolling Stone in the mid-sixties.

Elton John shared his memorable first encounter with My Sweet Lord, recalling how he heard it while riding in a taxi. He described it as the final great single of the era, saying, “I thought, ‘Oh my God,’ and I got chills. You know when a record starts on the radio, and it’s great, and you think, ‘Oh, what is this, what is this, what is this?’”

In addition to this musical milestone, today also commemorates a fascinating event from 64 years ago—the infamous “laughter epidemic” in Kashasha, Tanzania. This peculiar phenomenon began at an all-girls school, where uncontrollable giggles erupted, making it challenging for teachers to continue their lessons. Psychologists suggest it was a case of mass psychogenic illness, lasting for several months.

What started with just three girls quickly spread throughout the school, impacting 95 of the 159 pupils aged 12 to 18, with symptoms ranging from a few hours to an astonishing 16 days. The teaching staff remained unaffected, but the laughter disrupted the learning environment, leading to the school’s closure on March 18.

The epidemic expanded to Nshamba, where many affected girls lived, resulting in laughter attacks among 217 villagers, mostly young people, during April and May. After reopening on May 21, the school had to close again by the end of June. In total, 14 schools and over 1,000 students experienced fits of hysterical laughter and giggling.

Some scientists propose that this laughter response was a reaction to stress, similar to how a mob mentality can arise during tumultuous events. Following Tanganyika’s independence in 1962, the pressure to succeed academically may have contributed to this unusual collective behavior, although research remains observational and speculative.