The British Museum, one of the world’s most iconic cultural institutions, continues to face mounting pressure over its retention of 16 significant historical artifacts that numerous countries and communities insist should be repatriated. As debates intensify in 2024, this standoff highlights the ongoing global conversation about colonial legacies, cultural ownership, and the ethics of museum collections.

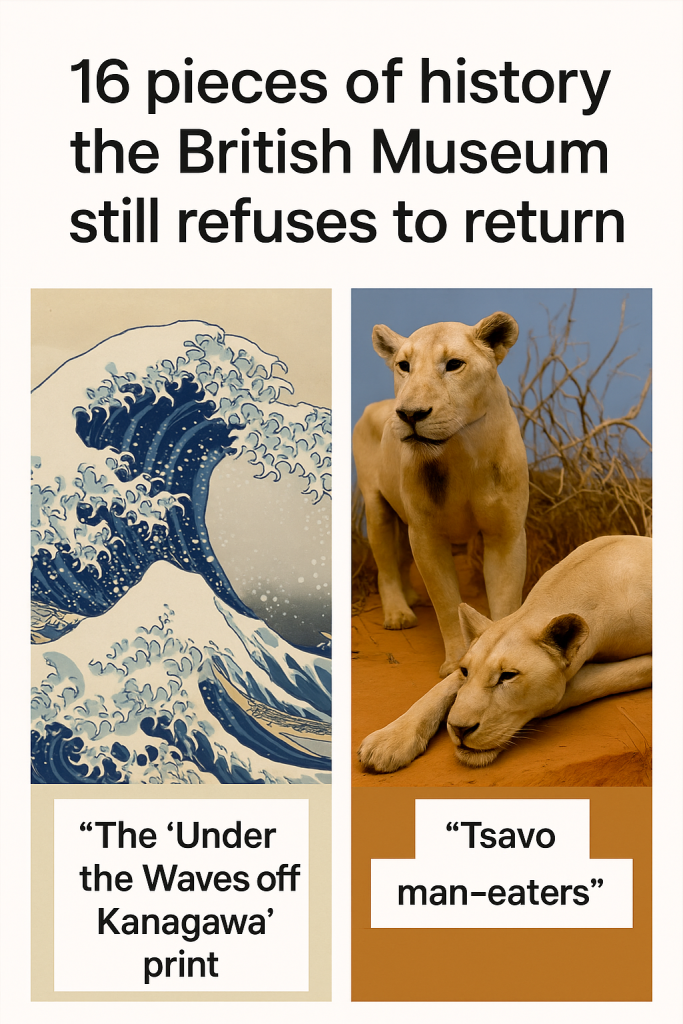

Among the contested items, two stand out for their cultural and historical significance: the woodblock print known as Under the Waves off Kanagawa and artifacts related to the Tsavo man-eaters, infamous for their menacing role in African colonial history.

Under the Waves off Kanagawa, often overshadowed by its more famous counterpart “The Great Wave off Kanagawa,” is a notable example of Japanese ukiyo-e art preserved within the British Museum’s vast Asian collection. Requests for its return have surfaced amid a wider push by Japanese cultural bodies to reclaim artworks acquired during periods of imperialism and war. Advocates argue that such pieces hold deep cultural and spiritual significance and rightfully belong in their places of origin to maintain cultural continuity and national identity.

The Tsavo man-eaters artifacts represent a darker chapter of colonial history. These items relate to the infamous man-eating lions that terrorized railway workers in Kenya in the late 19th century. The artifacts, including teeth and skins, currently held by the British Museum, have been the subject of increasing calls for repatriation by Kenyan authorities. They argue that these objects are not mere curiosities but pivotal cultural symbols representing local history and colonial resistance narratives.

Despite numerous formal appeals and growing international awareness advocating for the return of these and other items, the British Museum has maintained its stance. The institution asserts that these artifacts are preserved in a way that allows global audiences to access and learn about diverse cultures and historic epochs. Their position reflects a broader argument within the museum sector: that museums function as custodians of global heritage, providing a neutral ground where shared human history is displayed and studied.

Nevertheless, this viewpoint faces sharp criticism. Many argue that retaining such artifacts perpetuates historical injustices and denies source communities the right to self-representation and cultural reclamation. The 16 pieces of history still withheld include objects spanning continents, epochs, and cultures, from African royal regalia and Native American sacred items to Southeast Asian religious sculptures and Middle Eastern antiquities.

Most recently, the discussions around these objects have gained fresh momentum alongside international movements calling for decolonization of museums and the restitution of cultural property. Activists emphasize that museums built on colonial acquisitions must engage in genuine dialogue with claimant nations and explore innovative solutions like long-term loans, joint custody agreements, or outright repatriation.

As the debate unfolds, the British Museum finds itself at the epicenter of a profound global reckoning. The resolution of these repatriation disputes has potential ramifications far beyond London, influencing how museums worldwide handle contested legacies and steward humanity’s shared past. Whether some or all of these 16 contested treasures will return to their places of origin remains an unresolved and potent question—one that underscores the complexities of cultural heritage in the 21st century.