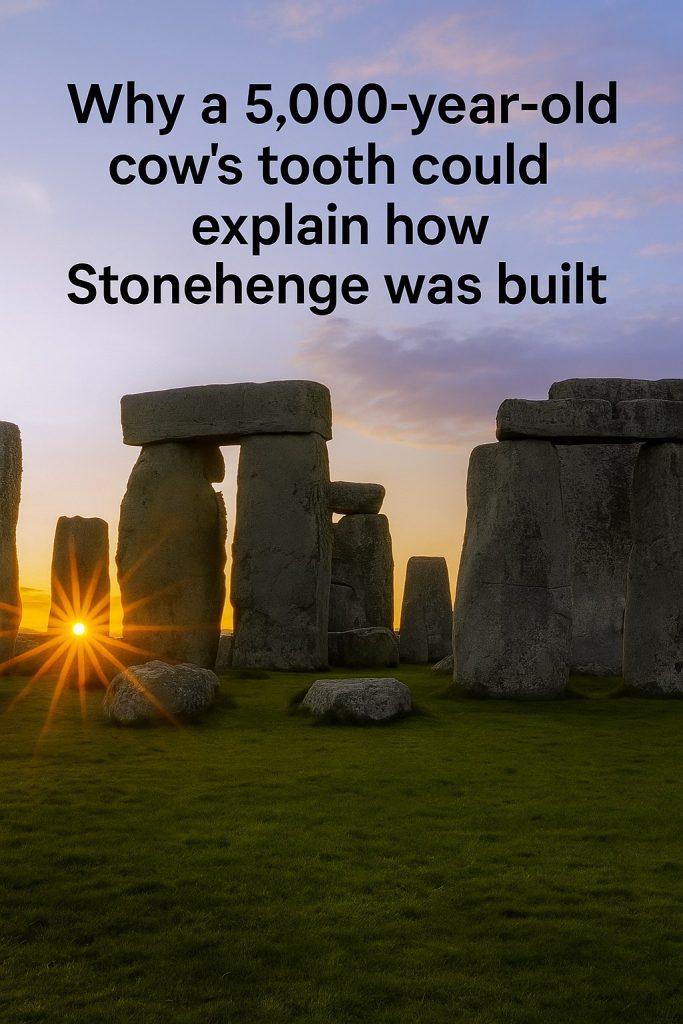

Archaeologists have made a surprising discovery that could shed new light on the ancient construction methods behind one of the world’s most enigmatic monuments, Stonehenge. A 5,000-year-old cow’s tooth, recently analyzed through advanced scientific techniques, is providing unprecedented insight into the origins and logistics of the monument’s building process.

Stonehenge, located in southern England, has long puzzled historians and researchers. Constructed during the Neolithic period, around 3000 to 2000 BCE, its massive standing stones have sparked countless theories about how and why it was built. Traditionally, research has focused on the stones themselves—where they came from, how they were transported, and what their purpose was. However, this cow’s tooth, discovered near the site, is opening a new window on the daily lives and practices of the people who built the stone circle.

How a Cow’s Tooth Became an Archaeological Game-Changer

The cow tooth was found during a recent excavation of ancient settlement layers adjacent to Stonehenge. Using isotopic analysis and microscopic dental wear examination, researchers determined that the tooth belonged to a domesticated cow alive approximately 5,000 years ago—the same era when the early stages of Stonehenge’s construction began. Notably, the chemical signature on the tooth suggests this cow grazed on plants containing specific minerals sourced from distant regions.

So, why does this matter? The unique mineral traces imply that the cattle herded around the monument were part of a sophisticated agricultural and transport network extending far beyond the immediate area. This challenges earlier assumptions that the builders were isolated locals operating on a small scale.

Implications for Stonehenge’s Construction Techniques

The tooth’s evidence suggests that ancient communities had developed complex systems—not only for herding and managing livestock but also possibly for resource sharing and coordinated labor efforts spanning multiple regions. Livestock, especially cattle, could have been crucial for hauling heavy stones, clearing land, and supporting large workforce gatherings with food and materials.

Moreover, the findings hint that the builders of Stonehenge might have employed animal-powered transportation methods far earlier than previously known. This raises the possibility that oxen or cattle were used to drag the massive sarsen stones across great distances, complementing human labor. The ability to mobilize and sustain large herds would have been a vital element in the logistical challenge of constructing the monument.

Enriching Our Understanding of Neolithic Britain

This discovery is more than just a footnote in Stonehenge research. It offers an intimate glimpse into the interconnectedness of prehistoric communities and their environment. The cow’s tooth acts as a tangible link between natural history and human engineering achievements, revealing how early farmers and herders contributed directly to one of the greatest architectural feats of prehistoric Europe.

As technology advances, insightful finds like this cow tooth encourage archaeologists to look beyond stone and bone fragments and explore the broader ecosystem that made monumental projects like Stonehenge possible. The continued exploration of animal remains, environmental data, and material culture promises to unravel more secrets of how our ancient ancestors shaped the world.

What’s Next?

The research team is planning further isotopic studies on additional animal remains from the region to map out ancient herd movements and trade routes in greater detail. Coupled with landscape archaeology and experimental reconstruction techniques, these efforts could dramatically change our understanding of Neolithic engineering and social organization.

In summary, this 5,000-year-old cow’s tooth might be small, but it carries huge significance—offering exciting new